Back in the Lab

Research ramp up across Columbia Engineering met with great enthusiasm

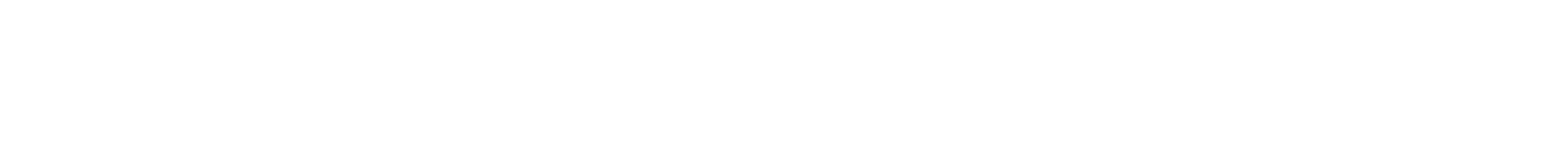

Student observing new protocols in the Ultrasound Elasticity and Imaging Laboratory.

With the dramatic reduction in COVID-19 cases in New York in recent weeks, labs across Columbia Engineering have been given the green light to resume operations.

The University’s Phase 1 reopening began on June 22, as officials rolled out stringent new protocols protecting researchers returning to campus. As a result, the majority of engineering labs are back up and running, albeit at no more than 33% capacity in order to support physical distancing. Occupancy levels will further expand in an upcoming second phase. In addition to maintaining reduced density, researchers are individually required to obtain a baseline SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic test, wear personal protective equipment, receive training from Columbia Environmental Health & Safety, and conduct daily symptom self-checks. Facilities are regularly sanitized every day by University Facilities and Operations and signage for traffic control and public health guidance are widely posted throughout the buildings. Research groups who can effectively conduct their research off campus are continuing to maintain their active research activities remotely.

“These new rules ensure that we’re prioritizing safety even as our labs resume breakthrough work on everything from sustainable energy to neurodegenerative diseases,” says Shih-Fu Chang, senior executive vice dean at Columbia Engineering. “Our community is not just meeting University guidelines for reopening; all our PIs are also implementing approved plans tailored to enhance productivity and safety for their individual circumstances.”

The Columbia Nano Initiative has further tightened its fastidious standards to ensure minimal disruptions.

Researchers say the recent announcement has been met with much enthusiasm.

“My students couldn’t wait to get back in the lab,” says Prof. Elisa Konofagou, who leads the Ultrasound Elasticity and Imaging Laboratory. “Although we have several projects that can be performed remotely with simulations and computer models, and some started building circuit boards et cetera at home, the majority of our work is validating those models with real experiments. Most of the novelty lies there—and, of course, the satisfaction.”

This spring Konofagou’s group was set to start clinical trials of a new ultrasound treatment they developed for Alzheimer’s. With the ramp up, they’ve now begun enrolling subjects in a clinical study that was more than a decade in the making.

During the downtime, Konofagou wasn’t alone in using the ramp-down to reflect on creative new approaches to bring back into the lab. Lightwave Research Lab head Prof. Keren Bergman took advantage of the hiatus to work with her team on remotely conducting data analysis and modeling, as well as thought experiments in design, system architecture—and intergroup dynamics.

“We also divided our team into multiple small subgroups focused on technical areas so as to maximize cross-group interactions,” Bergman says. “And we attempted to duplicate as much as possible the important informal technical discussions we have.”

After reorganizing work stations for maximum physical separation, the reopening now gives them the chance to put these new ideas to the test.

Like other faculty members, Bergman has been in close contact with her group throughout the past few months, monitoring their wellbeing as well as their academic progress.

Steingart's lab developed an app to track occupancy.

These new rules ensure that we’re prioritizing safety even as our labs resume breakthrough work on everything from sustainable energy to neurodegenerative diseases.

A similar impetus motivated Prof. Dan Steingart’s team to add their own new protocol to the list. This group of earth, environmental, and chemical engineers created an app to seamlessly track whenever a lab member enters or leaves the premises. It also attempts to tally not only how many people are currently in the room but also the total number over the course of a day.

Much of his group’s work in next-generation energy storage with the Columbia Electrochemical Energy Center can readily be pursued “out of office,” using their online-first data acquisition and analysis system. But that didn’t stop them from making a few improvements.

“We ordered some new equipment to help us study side reactions in batteries, which works well with Phase 1 scheduling because one can come in, set up experiments, and then monitor remotely until they’re finished,” Steingart notes. They set up “tag teams” as well, so that students can assist each other in keeping everyone’s experiments smoothly on track. “In this way, we can get started without taking crucial space from healthcare workers on subways and buses.”

The Sia lab rapidly moved to focus on COVID-19.

Not all labs ceased on-site work during the hiatus. Prof. Sam Sia, an expert in microfluidics and point-of-care diagnostics and therapeutics, never completely shuttered his lab: having previously developed technology for detecting nucleic acids and antibodies, his group instead rapidly moved their focus to COVID-19 and similar conditions.

“We’ve been working on coronavirus diagnostics at an intense pace, but the experimental portions of all non-coronavirus projects were shut down” Sia says. The ramp up now allows his group to pick up where they left off on other key projects. “We’re starting back up a DARPA project on wound healing from before the pandemic.”

Among the many new safety protocols are individual bottles of hand sanitizer with the Columbia Engineering logo that the school is distributing to each researcher.

Meanwhile, over at the Columbia Nano Initiative’s (CNI) one of the most spotless places on campus has further tightened its fastidious standards to ensure minimal disruptions.

“So far we haven’t had a problem providing access to equipment for whoever’s needed it,” says Dr. Nava Ariel-Sternberg, director of CNI shared labs, which consist of a Clean Room as well as labs for materials characterization and electron microscopy.

“The world has changed and our lab users understand that working in a shared lab space has to involve some changes as well,” she adds. “All our users have been very supportive and understanding, and I believe that they appreciate all the hard work and efforts they see us making so they can do their research.”